In part 2 of the multiwave oscillator impedance (MWO) measurements we take a look at the high frequency impedance characteristics Z11 for the MWO resonator rings (top-load). The MWO Tesla style drive coil measured in part 1 needs to be separated from the MWO top-load for this type of measurement, because the impedance and load of the drive coil masks out any resonant features at higher frequencies, making it impossible to measure the MWO when connected to the top of the secondary coil and measured at the input to the primary coil.

Experiments, operation, and measurements in Tesla coil based systems, and indeed in my own research regarding the displacement and transference of electric power, are normally limited to experimental apparatus which operates at maximum in the HF band < 30Mc/s of the electromagnetic spectrum. At 30Mc/s the corresponding wavelength λ is 10m. As a standard rule of thumb in high frequency or RF measurements the feature size of the element under measurement should be < λ/10 to be considered as a discrete lumped element in the system, and therefore not subject to impedance transformations through transmission line characteristics or other distributed network characteristics. At the upper end of the HF band this means that active measurement regions < 1m in size or length can be considered to have only small, if any, transformation and change on the impedance outside of that attributed with its discrete lumped element network.

As we progress to higher frequency measurements in the VHF band (30 – 300Mc/s) and even above in the UHF band (300Mc/s – 3Gc/s) very great care needs to be taken regarding the length and size of cabling and connections, the feature sizes of components within the measurement network, the impedance match or mismatch between transmission line sections and discrete components, and any other stray, parasitic, or proximity effects arising from boundary conditions that are both metallic or dielectric in nature. Accordingly, much greater care and attention needs to be taken to calibrate as accurately as possible directly to the plane of measurement, and then to normalise out measurement effects between the calibration plane and measurement apparatus.

In this part we are concerned with measurement up to ~1Gc/s (λ = 30cm), and where the λ/10 length is only 3cm. At λ/4 quarter-wavelength we would expect to see a complete impedance transformation along a transmission line from a very low impedance (short-circuit) at the output of the source generator to a very high impedance (open-circuit) at the end of a wire or measurement plane. Accordingly we need to keep connections small and efficient which represents in itself a unique challenge when connecting to the MWO rings, which at UHF frequencies represent a large distributed network of inter-connected transmission line elements, with complex boundary conditions. Subsequent parts will look at the MWO rings as an antenna with corresponding radiation resistance and defined radiation pattern and particularly in relation to the transmitter – receiver configuration of the complete MWO system.

For this part, and to measure as accurately as possible Z11 for the MWO rings directly, and up to frequencies in the order of ~1Gc/s, it was necessary to make a connecting jig that allowed for extension of the reference plane from the VNA-SDR directly to the mounting spheres of the outer driven ring of the MWO. Figures 1 below show the measurement setup, signal feed adapter, MWO mounting jig, calibration elements, and overall arrangement of the high frequency impedance measurement apparatus.

To view the large images in a new window whilst reading the explanations click on the figure numbers below.

Fig 1.1. Shows the overall measurement setup with the VNA-SDR connected to the MWO mounting jig by a short SMA terminated RG316 cable, and the other end to the signal feed adapter (SFA), and standard calibration elements.

Fig 1.2. The SFA mounts directly to high voltage terminals, that are themselves connected to the brass mounting bolts used to hold the MWO rings to the jig. The jig is constructed predominantly in nylon 66 with a wooden internal support for strength inside the main jig support column. The high frequency path length and connection effects are normalised out by extending the calibration reference plane right to the brass bolt mounting points for the MWO outer ring. The SFA in this case is used with shorted series capacitance feed, and is balanced with equal weights of copper on the positive and negative feed paths, which includes the SMA connectors and the RG316 cable to the VNA-SDR. Equal weights of copper, or more accurately at high frequencies (> 3Mc/s), equal volumes of copper assist in balancing the boundary conditions for the electric and magnetic fields of induction and so reducing impedance mismatches in the signal feed path. As for part 1 an SFA with 3Gc/s balun was also tried but found to be largely unsuccessful in the small signal measurements due to the masking of high frequency detail, which results from the balun coupling transformer dominating the frequency characteristics in the mid to high-band frequencies.

Fig 1.3. The calibration elements fit directly onto the end of the MWO brass mounting bolts. With no element attached the mounts are calibrated for open-circuit, a single-sided pcb element is used for the short-circuit, and a single-sided pcb with 50Ω surface mount resistor in the centre for the calibrated load.

Fig 1.4. Shows the MWO rings mounted to the measurement jig.

Fig 1.5. An improvement to the calibration procedure removed the SMA connecting cable by mounting the VNA-SDR directly to the SFA by SMA coupler. In this configuration some additional resonant features were removed from the normalised calibration results.

Fig 1.6. The final measurement setup for the high frequency MWO impedance measurements with VNA-SDR directly mounted to the SFA, which is in turn directly mounted to the jig, and where the calibration plane is at the point where the MWO outer ring brass balls meet the brass mounting bolts.

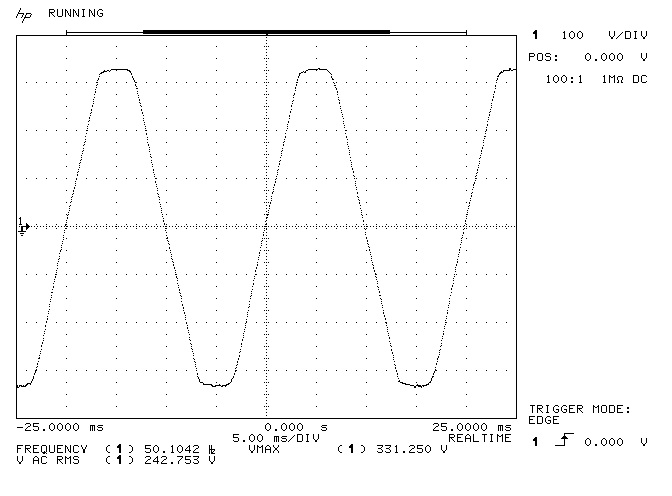

Figures 2 below show the Z11 impedance characteristics of the calibrated reference plane and the lower high frequency measurement band 100kc/s – 500Mc/s. The entire high frequency band was split into two in order to best comply with the calibration bands within the VNA-SDR instrument. At 500Mc/s the instrument internally changes reference method and level, and sensitive measurements cross-band are not recommended. Therefore the measurements are calibrated into a lower band 100kc/s-500Mc/s and an upper band 500Mc/s – 1.3Gc/s.

Fig 2.1. Calibration for the 50Ω reference element over the band. Markers M1, M3, and M5 show the consistent calibration across most parts of the band. At M2 at 138Mc/s and M4 at 377Mc/s there are resonances within the calibrated signal path which are too significant to normalise out. These points will need to be factored into the measurement results to remove features of interest, if any, that correspond at these frequencies. At these 2 points features in the results are considered measurement artefacts that arise due to the measurement system and inter-connection between the instrument and the MWO rings at the calibration plane.

Fig 2.2. Shows the rich range of resonant features that result from the MWO rings and their inter-action across the band. In this first result markers M1 – M12 are used to identify the lower 12 set of features, and in the next set of results the upper 12 set of features. There is no corresponding feature at 138Mc/s as seen in the calibration scan, and hence this point does not need to to be removed from the results. The first 250Mc/s of the results show a number of strong resonant points indicated by the large phase changes occurring at M4, M6, M8, and M9, and most likely attributed to resonances in the outer few rings of the MWO. There are also smaller phase inversions across the first half of the results occurring at M1, M2, M5, M7, M10, and M11 which most likely arise due to resonant inter-actions between the outer few rings of the MWO. At M12 287Mc/s a large peak change in |Z11| occurs for a very small phase inversion, which would likely indicate where the outer drive ring of the MWO becomes self-resonant, in a similar way to that of the primary in the drive coil which becomes self-resonant at ~38MC/s. The point at M12 may also correspond to the 2nd harmonic of this point with the fundamental occurring at M8, this however being less likely due to the very low impedance swing at M8 to ~6.9Ω indicating that M8 is more likely to be associated with the fundamental resonance of one of the few outer rings, but not the driven ring.

Fig 2.3. Shows the markers on the upper 12 set of features. At M10 375Mc/s there is a large resonance, the only in the upper 250Mc/s of the results, which also very closely corresponds to the calibration feature noted in Fig 2.1. at M4 at 377Mc/s. The close correspondence of these two points means that the feature at M10 needs to be attributed to a strong resonance in the calibration path which could not effectively be normalised out by the calibration procedure. Otherwise in the upper part of the results there are some small phase inversions at M11 and M12 which could be tentatively linked to the fundamental resonant frequencies of some the rings further into the MWO centre. In the upper part of the results we start to see a general masking, smearing, and suppression of further detail, not necessarily because the detail is not there, but rather the coupling between rings is not sufficiently loose to allow for the natural resonance of each ring to be reflected in the results, and combined with rapidly increasing losses, large reductions in Q, and decreasing amplitude of oscillation as the results move towards the centre of the MWO. This could be further tested and measured by decreasing the coupling factor between each of the rings by changing the structure of the MWO from a flat set of rings to a cone configuration, where each of the rings retain the same diameter but are separated further apart vertically on the cone yielding a three-dimensional MWO structure. The other way to measure and assess this further is to remove every other ring in the flat MWO so reducing the coupling between rings and also reducing the large number of inter-active resonances. The process of starting with one ring inside the driven ring and subsequently adding ring by ring taking an impedance scan with each ring, would also assist in clarifying which fundamentals occur from which rings, and which features occur due to cross-coupling between the rings.

Figures 3 below show the Z11 impedance characteristics of the calibrated reference plane and the upper high frequency measurement band 500Mc/s – 1.3Gc/s.

Fig 3.1. The calibration of the upper high frequency band shows very good consistency and results for the 50Ω reference load up to M3 at 1096Mc/s. Above this point the signal attenuation is such that the returned measurement currents to the VNA-SDR are so small as to be falling outside the lower dynamic range of the instrument, and hence the results become progressively more inaccurate and noisy. It is to be noted that the base 50Ω reference load can still be extrapolated visually to the end point ar 1300Mc/s. However, above ~1Gc/s the results on this measurement apparatus and setup are considered to not be of further use as can be more clearly seen in the next result.

Fig 3.2. At the lower end of this band markers M1 – M5 continue the upper band of the previous results in most likely showing fundamental resonances and maybe even some inter-actions between some of the more inner rings of the MWO e.g. rings 4-7. It is unlikely that any details can easily be discerned for the inner rings 8-11 where the signal reflections are very small, and stronger coupling between rings has largely smeared out the detail and suppressed the Q of the response.

Overall the high frequency impedance measurements have presented a wealth of detail particularly in the lower part of the band and with discernible results being contributed to by as many as the first 6-8 rings inside the outer driven ring. It is also clear that cross-coupling between rings will contribute to very high frequency components to be emitted from the MWO, even though such detail is largely outside of the scope and dynamic range of the measurement technique used here. A useful comparison measurement would be to look at the range of frequency components generated during normal high tension operation of the complete MWO system, using a spectrum analyser instrument with capabilities into the Gc/s range. The high frequency impedance characteristics still need to be measured for the complete MWO system where both transmitter and receiver are connected to the system, which will be reported in a subsequent part.

1. Vril Science, Lahkovsky Multiwave Oscillator, 2019, Vril